Émile Zola

Appearance

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (2 April 1840 – 29 September 1902) was a French novelist, playwright, journalist, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of theatrical naturalism.

Quotes

[edit]

- There are two men inside the artist, the poet and the craftsman. One is born a poet. One becomes a craftsman.

- Letter to Paul Cézanne (16 April 1860), as published in Paul Cézanne: Letters (1995) edited by John Rewald.

- I am little concerned with beauty or perfection. I don't care for the great centuries. All I care about is life, struggle, intensity. I am at ease in my generation.

- "My Hates" (1866).

- One forges one's style on the terrible anvil of daily deadlines.

- Le Figaro (1881) as quoted in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (1999) by Elizabeth Knowles and Angela Partington, p. 840.

- Everything is only a dream.

- Le Rêve [The Dream] (1888).

- Paris flared — Paris, which the divine sun had sown with light, and where in glory waved the great future harvest of Truth and of Justice.

- Paris (1898) Last of Les Trois Villes [The Three Cities] trilogy.

- Dreyfus is innocent. I swear it! I stake my life on it — my honor! At this solemn moment, in the presence of this tribunal which is the representative of human justice, before you, gentlemen of the jury, who are the very incarnation of the country, before the whole of France, before the whole world, I swear that Dreyfus is innocent. By my forty years of work, by the authority that this toil may have given me, I swear that Dreyfus is innocent. By all I have now, by the name I have made for myself, by my works which have helped for the expansion of French literature, I swear that Dreyfus is innocent. May all that melt away, may my works perish if Dreyfus be not innocent! He is innocent. All seems against me — the two Chambers, the civil authority, the military authority, the most widely-circulated journals, the public opinion which they have poisoned. And I have for me only an ideal of truth and justice. But I am quite calm; I shall conquer. I was determined that my country should not remain the victim of lies and injustice. I may be condemned here. The day will come when France will thank me for having helped to save her honor.

- Appeal for Dreyfus delivered at his trial for libel (22 February 1898).

- If you shut up truth and bury it under the ground, it will but grow, and gather to itself such explosive power that the day it bursts through it will blow up everything in its way.

- As quoted in Dreyfus: His Life and Letters (1937) edited by Pierre Dreyfus, p. 175.

- If you ask me what I came to do in this world, I, an artist, I will answer you: I am here to live out loud!

- As quoted in Writers on Writing (1986) by Jon Winokur.

- The artist is nothing without the gift, but the gift is nothing without work.

- As quoted in Wisdom for the Soul: Five Millennia of Prescriptions for Spiritual Healing (2006) by Larry Chang , p. 55.

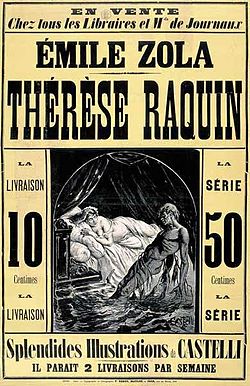

Thérèse Raquin (1867; 1868)

[edit]

- A writer of great talent, to whom I complained of the little sympathy I have met with, made me this profound answer: "You have an immense fault which will close all doors against you: you cannot converse for two minutes with a fool without showing him that he is one."

- Preface to the 2nd ed., 1868 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- The critics greeted this book with a churlish and horrified outcry. Certain virtuous people, in newspapers no less virtuous, made a grimace of disgust as they picked it up with the tongs to throw it into the fire. Even the minor literary reviews, the ones that retail nightly the tittle-tattle from alcoves and private rooms, held their noses and talked of filth and stench. I am not complaining about this reception; on the contrary I am delighted to observe that my colleagues have such maidenly susceptibilities.

- Preface to the 2nd ed., 1868 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1962)

- Thérèse, residing in damp obscurity, in gloomy, crushing silence, saw life expand before her in all its nakedness, each night bringing the same cold couch, and each morn the same empty day.

- Ch. 3 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- Thérèse could not find one human being, not one living being among these grotesque and sinister creatures, with whom she was shut up; sometimes she had hallucinations, she imagined herself buried at the bottom of a tomb, in company with mechanical corpses, who, when the strings were pulled, moved their heads, and agitated their legs and arms.

- Ch. 4 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- The only ambition of this great powerful frame was to do nothing, to grovel in idleness and satiation from hour to hour. He wanted to eat well, sleep well, to abundantly satisfy his passions, without moving from his place, without running the risk of the slightest fatigue.

- Ch. 5 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- She made a savage, angry effort at revolt, and, then all at once gave in. They exchanged not a word. The act was silent and brutal.

- Ch. 6 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- They have stifled me with their middle-class gentleness, and I can hardly understand how it is that there is still blood in my veins. I have lowered my eyes, and given myself a mournful, idiotic face like theirs. I have led their deathlike life.

- Ch. 7 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- The young woman seemed to take pleasure in being bold and shameless. She had no hesitation, no fear whatsoever. She threw herself into adultery with a sort of vigorous sincerity, defying danger and doing so with a sort of vanity in her defiance.

- Ch. 7 (tr. Adam Thorpe, 2013)

- Il a besoin de cette femme pour vivre comme on a besoin de boire et de manger.

- This woman was as necessary to his life as eating and drinking.

- Ch. 9 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- L'idée de la mort, jetée avec désespoir entre deux baisers, revenait implacable et aiguë.

- The idea of death, blurted out in despair between a couple of kisses, returned implacable and keen.

- Ch. 9 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- Parfois, ils se forçaient à l’espérance, ils cherchaient à reprendre les rêves brûlants d’autrefois, et ils demeuraient tout étonnés, en voyant que leur imagination était vide.

- Sometimes, forcing themselves to hope, they sought to resume the burning dreams of other days, and were quite astonished to find they had no imagination.

- Ch. 16 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- When they seated themselves in their carriage, they seemed to be greater strangers than before.

- Ch. 20 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- The sort of remorse Laurent experienced was purely physical. His body, his irritated nerves and trembling frame alone were afraid of the drowned man. His conscience was for nothing in his terror. He did not feel the least regret at having killed Camille. When he was calm, when the spectre did not happen to be there, he would have committed the murder over again, had he thought his interests absolutely required it.

- Ch. 22 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- In the sudden change that had come over her heart, she no longer recognised herself.

- Ch. 26 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- Nothing could be more heartrending than this mute and motionless despair.

- Ch. 26 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- For Madame Raquin, there was such a fathomless depth in this thought, that she could neither reason it out, nor grasp it clearly. She experienced but one sensation, that of a horrible disaster; it seemed to her that she was falling into a dark, cold hole. And she said to herself: "I shall be smashed to pieces at the bottom."

- Ch. 26 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- After a time, she believed in the reality of this comedy.

- Ch. 29 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- He knew that henceforth, all his days would resemble one another, and bring him equal suffering. And he saw the weeks, months and years gloomily and implacably awaiting him, coming one after the other to fall upon him and gradually smother him.

- Ch. 30 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- Lorsque l'avenir est sans espoir, le présent prend une amertume ignoble.

- When there is no hope in the future, the present appears atrociously bitter.

- Ch. 30 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- The couple fell one atop of the other, struck down, finding consolation, at last, in death.

- Ch. 32 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

La Fortune des Rougon (1871)

[edit]- When a peasant begins to feel the need for instruction, he usually becomes fiercely calculating.

- Ch. 2 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2012)

- The Revolution of 1848 found all the Rougons on the lookout, frustrated by their bad luck, and ready to use any means necessary to advance their cause. They were a family of bandits lying in wait, ready to plunder and steal.

- Ch. 2 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2012)

- ... il y avait en elle un manque d'équilibre entre le sang et les nerfs, une sorte de détraquement du cerveau et du cœur, qui la faisait vivre en dehors de la vie ordinaire, autrement que tout le monde.

- ... there was a lack of equilibrium between her nerves and her blood, a disorder of the brain and heart which made her lead a life out of the ordinary, different from that of the rest of the world.

- Ch. 2 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1898)

- From that time onwards he seemed to feel out of place in Plassans. He would wander through the streets like a lost soul. At last he made a sudden decision, and left for Paris.

- Ch. 2 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2012)

- Kings may usurp thrones, republics may be established, but the town scarcely stirs. Plassans sleeps while Paris fights.

- Ch. 3 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2012)

- A new dynasty is never founded without a struggle. Blood makes good manure. It will be a good thing for the Rougon family to be founded on a massacre, like many illustrious families.

- Ch. 3 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2012)

- Ce fut un naïf, un naïf sublime, resté sur le seuil du temple, à genoux devant des cierges qu’il prenait de loin pour des étoiles.

- He was one of the simple-minded, one whose simplicity was divine, and who had remained on the threshold of the temple, kneeling before the tapers which from a distance he took for stars.

- Ch. 4 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1898)

- When lovers kiss on the cheeks, it is because they are searching, feeling for one another’s lips. Lovers are made by a kiss.

- Ch. 5 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1898)

- Prends garde, mon garçon, on en meurt.

- Be careful, my boy; this kind of thing kills people.

- Ch. 5 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2012)

- They kissed each other again and fell asleep. The patch of light on the ceiling now seemed to be assuming the shape of a terrified eye, staring unblinkingly at the pale, slumbering couple, who now reeked of crime under their sheets, and were dreaming that they could see blood raining down in big drops and turning into gold coins as they landed on the floor.

- Ch. 6 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2012)

- For a moment he thought he could see, in a flash, the future of the Rougon-Macquart family, a pack of wild, satiated appetites in the midst of a blaze of gold and blood.

- Ch. 7 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2012)

- Puis le moment de la séparation sonnait, Miette remontait sur son mur. Elle lui envoyait des baisers. Et il ne la voyait plus. Une émotion terrible le prit à la gorge: il ne la verrait plus jamais, jamais.

- Then the hour of separation came, and Miette climbed the wall again and threw him a kiss. And he saw her no more. Emotion choked him at the thought: he would never see her again—never!

- Ch. 7 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1898)

- Endless love and voluptuous appetite pervaded this stifling nave in which settled the ardent sap of the tropics. Renée was wrapped in the powerful bridals of the earth that gave birth to these dark growths, these colossal stamina; and the acrid birth-throes of this hotbed, of this forest growth, of this mass of vegetation aglow with the entrails that nourished it, surrounded her with disturbing odours. ... But amid this strange music of odours, the dominant melody that constantly returned, stifling the sweetness of the vanilla and the orchids' pungency, was the penetrating, sensual smell of flesh, the smell of lovemaking escaping in the early morning from the bedroom of newlyweds.

- Ch. 1 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2004)

- Etre pauvre à Paris, c'est être pauvre deux fois.

- To be poor in Paris, is to be doubly poor.

- Ch. 2 (tr. Anonymous, 1885)

- She never spoke of her husband, nor of her childhood, her family, or her personal concerns. There was only one thing she never sold, and that was herself.

- Ch. 2 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2004)

- The Empire had just been proclaimed, after that famous journey during which the Prince President had succeeded in arousing the enthusiasm of some Bonapartist departments. Silence reigned both at the tribune and in the press. Society, saved once more, was congratulating itself and indolently resting, now that a strong government was protecting it and relieving it even of the trouble of thinking and of attending to its own business.

- Ch. 2 (tr. Anonymous, 1885)

- The Empire was on the point of turning Paris into the bawdy house of Europe. The gang of fortune-seekers who had succeeded in stealing a throne required a reign of adventures, shady transactions, sold consciences, bought women, and rampant drunkenness.

- Ch. 2 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2004)

- He was twenty, and already there was nothing left to surprise or disgust him. He had certainly dreamt of the most extreme forms of debauchery. Vice with him was not an abyss, as with certain old men, but a natural, external growth.

- Ch. 3 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2004)

- Those harlot eyes were never lowered; they courted pleasure, a pleasure without fatigue which one summons and receives.

- Ch. 3 (tr. Anonymous, 1885)

- This was the time when the rush for the spoils filled a corner of the forest with the yelping of hounds, the cracking of whips, the flaring of torches. The appetites let loose were satisfied at last, shamelessly, amid the sound of crumbling neighbourhoods and fortunes made in six months. The city had become an orgy of gold and women.

- Ch. 3 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2004)

- Vice, coming from above, flowed along the gutters, spread itself out in the sheets of ornamental water, re-ascended in the fountains of the public gardens to fall again on to the roofs in a fine penetrating rain.

- Ch. 3 (tr. Anonymous, 1885)

- À cette heure, elle voulut le mal, le mal que personne ne commet, le mal qui allait emplir son existence vide et la mettre enfin dans cet enfer, dont elle avait toujours peur, comme au temps où elle était petite fille.

- At that hour she desired sin, the sin which no one commits, the sin which would fill her empty life, and finally set her in that hell of which she was still afraid, just as she had been when she was a little girl.

- Ch. 5, sec. 4 (tr. Anonymous, 1885)

- Sin became a luxury, a flower set in her hair, a diamond fastened on her brow.

- Ch. 5, sec. 5 (tr. Anonymous, 1885)

Le Ventre de Paris (1873)

[edit]- Paris, pareil à un pan de ciel étoilé tombé sur un coin de la terre noire, lui apparut sévère et comme fâché de son retour.

- Paris, like a patch of starlit sky that had fallen upon the black earth, seemed to him quite forbidding, as though angered by his return.

- Ch. 1 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2007)

- Cependant Quenu se rappelait une phrase de Charvet, cette fois, qui déclarait que « ces bourgeois empâtés, ces boutiquiers engraissés, prêtant leur soutien à un gouvernement d’indigestion générale, devaient être jetés les premiers au cloaque. » C’était grâce à eux, grâce à leur égoïsme du ventre, que le despotisme s’imposait et rongeait une nation.

- At this moment Quenu called to mind a sentence of Charvet’s, asserting that "the bloated bourgeois, the sleek shopkeepers, who backed up that Government of universal gormandising, ought to be hurled into the sewers before all others, for it was owing to them and their gluttonous egotism that tyranny had succeeded in mastering and preying upon the nation."

- Ch. 3 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1896)

- "Good gracious!" she exclaimed, "she’s been more than an hour in there! When the priests set about cleansing her of her sins, the choir-boys have to form in line to pass the buckets of filth and empty them in the street!"

- Ch. 5 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1896)

- As they were all rather short of breath by this time, it was the camembert they could smell. This cheese, with its gamy odour, had overpowered the milder smells of the marolles and the limbourg; its power was remarkable. Every now and then, however, a slight whiff, a flute-like note, came from the parmesan, while the bries came into play with their soft, musty smell, the gentle sound, so to speak, of a damp tambourine. The livarot launched into an overwhelming reprise, and the géromé kept up the symphony with a sustained high note.

- Ch. 5 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2007)

- Respectable people... What bastards!

- Ch. 6 (tr. Brian Nelson, 2007)

L'Assommoir (1876; 1877)

[edit]

- Nana was a great coquette. She did not always wash her feet, but she wore such tight boots that she suffered a perfect martyrdom; and if anyone questioned her, seeing her face grow purple, she answered that she had a stomach-ache, so as not to confess her coquetry.

- Ch. 11 (tr. Arthur Symons, 1895)

- They called her 'the chicken', for she had in truth the soft flesh and country freshness of a chicken.

- Ch. 11 (tr. Arthur Symons, 1895)

Une page d'amour (1878)

[edit]- With eyes again dreamily gazing upward, Hélène remained plunged in reverie. She was the Lady Rowena; she loved with the serenity and intensity of a noble mind. That spring morning, that great, gentle city, those early wall-flowers shedding their perfume on her lap, had little by little filled her heart with tenderness.

- Pt. 1, ch. 5 / Ch. 5 (tr. C. C. Starkweather, 1905)

- How she had cheated herself with her integrity and nice honor, which had girt her round with the empty joys of piety! No, no; she had had enough of it; she wished to live!

- Pt. 2, ch. 5 / Ch. 10 (tr. C. C. Starkweather, 1905)

- All Paris was now illumined. The tiny dancing flames had speckled the sea of shadows from one end of the horizon to the other, and now, as in a summer night, millions of fixed stars seemed to be serenely gleaming there. Not a puff of air, not a quiver of the atmosphere stirred these lights, to all appearance suspended in space. Paris, now invisible, had fallen into the depths of an abyss as vast as a firmament.

- Pt. 3, ch. 5 / Ch. 15 (tr. C. C. Starkweather, 1905)

- Hélène slowly surveyed the room. In this respectable society, amongst these apparently decent middle-class people, were there none but faithless wives? With her strict provincial morality, she was amazed at the licensed promiscuity of Parisian life.

- Pt. 4, ch. 1 / Ch. 16 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1957)

- Quand Hélène revint [...] elle pensait que jamais ils ne s’étaient moins aimés que ce jour-là.

- When Hélène came back, ... she said to herself that they had never loved one another less than that day.

- Pt. 4, ch. 5 / Ch. 19 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1957)

- It was always the same; other people gave up loving before she did. They got spoilt, or else they went away; in any case, they were partly to blame. Why did it happen so? She herself never changed; when she loved anyone, it was for life. She could not understand desertion; it was something so huge, so monstrous that the notion of it made her little heart break.

- Pt. 5, ch. 1 / Ch. 20 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1957)

- Est-ce qu'une femme a besoin de savoir jouer et chanter? Ah! mon petit, tu es trop bête... Nana a autre chose, parbleu! et quelque chose qui remplace tout.

- Must a woman know how to act and sing? Oh, my chicken, you're too stoopid: Nana has other good points, by Heaven!—something which is as good as all the other things put together.

- Ch. 1 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- Tout d’un coup, dans la bonne enfant, la femme se dressait, inquiétante, apportant le coup de folie de son sexe, ouvrant l’inconnu du désir. Nana souriait toujours, mais d’un sourire aigu de mangeuse d’hommes.

- All of a sudden, in the good-natured child the woman stood revealed, a disturbing woman with all the impulsive madness of her sex, opening the gates of the unknown world of desire. Nana was still smiling, but with the deadly smile of a man-eater.

- Ch. 1 (tr. George Holden, 1972)

- Wasn't it true that the moment two women were together in the presence of their lovers their first idea was to do one another out of them? It was a law of nature!

- Ch. 4 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- Both women, looking different ways, kept shrugging their shoulders, and asking themselves how the deuce the other could tell such woppers!

- Ch. 4 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- The air there was heavy with the somnolence which accompanies a long vigil, and the lamps cast a wavering light, whilst their burnt-out wicks glowed red within their globes. The ladies had reached that vaguely melancholy hour when they felt it necessary to tell each other their histories.

- Ch. 4 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- The night threatened to end in the unloveliest way. In a corner by themselves, Maria Blond and Léa de Horn had begun squabbling at close quarters, the former accusing the latter of consorting with people of insufficient wealth.

- Ch. 4 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- She offered herself to him with that quiet expression which is peculiar to a good-natured courtesan.

- Ch. 4 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- He was a young dandy, and his habiliments, even to his gloves, were entirely yellow.

- Ch. 5 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- Ce fut une jouissance mêlée de remords, une de ces jouissances de catholique que la peur de l’enfer aiguillonne dans le péché.

- He experienced keen pleasure mingled with remorse, the kind of pleasure known only to Catholics who, in the midst of sin, are goaded by the fear of hell.

- Ch. 5 (tr. Lowell Blair, 1964)

- Madame Jules was a woman of no age. She had the parchment skin and changeless features peculiar to old maids whom no one ever knew in their younger years.

- Ch. 5 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- Satin occupied a couple of rooms, which a chemist had furnished for her in order to save her from the clutches of the police; but in little more than a twelvemonth she had broken the furniture, knocked in the chairs, dirtied the curtains, and that in a manner so furiously filthy and untidy, that the lodgings seemed as though inhabited by a pack of mad cats.

- Ch. 8 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- Amid that company of gentlemen with the great names and the old upright traditions;, the two women sat face to face, exchanging tender glances, conquering, reigning, in tranquil defiance of the laws of sex, in open contempt for the male portion of the community. The gentlemen burst into applause.

- Ch. 10 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- Great disorders lead to great conversions. Providence would have its opportunity.

- Ch. 12 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- Existence is so bitter for every one of us! Ought we not to forgive others much, my friend, if we wish to merit forgiveness ourselves?

- Ch. 12 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- A ruined man fell from her hands like a ripe fruit, to rot on the ground by himself.

- Ch. 13 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- Alors, Nana, tout de suite, entama La Faloise. Il postulait depuis longtemps l'honneur d'être ruiné par elle, afin d'être parfaitement chic.

- Then Nana started on la Faloise at once. He had for some time been longing for the honour of being ruined by her in order to put the finishing stroke on his smartness.

- Ch. 13 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- At every mouthful Nana swallowed an acre.

- Ch. 13 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- The rage for debasing things was inborn in her. It did not suffice her to destroy them, she must soil them too.

- Ch. 13 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

- Like those antique monsters whose redoubtable domains were covered with skeletons, she rested her feet on human skulls. She was ringed round with catastrophes.

- Ch. 13 (tr. Victor Plarr, 1895)

Pot-Bouille (1882)

[edit]

- When younger, he had been fun-loving to the point of tedium.

- Ch. 1 (tr. Brian Nelson, 1999)

- Her anger was rekindled.

"You see, I keep it to myself, but, oh! it’s more than I can stand. Don’t say anything, sir; don’t say anything, or I’ll explode!"

He said nothing, and she exploded all the same.- Ch. 2 (tr. Brian Nelson, 1999)

- The shelves had the melancholy emptiness and the false luxury of families where inferior meat is purchased so as to be able to put flowers on the table.

- Ch. 2 (Tr. Anonymous, 1885)

- "Those beasts have everything and we get nothing—not even a crust if we’re starving! The only thing they’re fit for is to be taken in! Just mark my words!"

Hortense and Berthe nodded, as though profoundly impressed by the wisdom of their mother’s pronouncements. She had long since convinced them of the absolute inferiority of men, whose sole function in life was to marry and to pay.- Ch. 5 (tr. Brian Nelson, 1999)

- She was cold by nature, self-love predominating over passion; rather than being virtuous, she preferred to have her pleasures all to herself.

- Ch. 12 (tr. Brian Nelson, 1999)

- Monsieur Josserand died very quietly—a victim of his own honesty. He had lived a useless life, and he went off, worthy to the last, weary of all the petty things in life, done to death by the heartless conduct of the only human beings he had ever loved.

- Ch. 17 (tr. Brian Nelson, 1999)

- He wept for truth which was dead, for Heaven which was void. Beyond the marble walls and gleaming jewelled altars, the huge plaster Christ had no longer a single drop of blood in its veins.

- Ch. 17 (tr. Brian Nelson, 1999)

Au Bonheur des Dames (1883)

[edit]

- La certitude d'avoir empêche de désirer.

- The certainty of having her as his wife prevented him from feeling any desire for her.

- Ch. 1 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1895)

- "You know, they’ll have their revenge."

"Who will?"

"The women, of course."- Ch. 2 (tr. Brian Nelson, 1995)

- It was the usual story of penniless young men, who think themselves obliged by their birth to choose a liberal profession and bury themselves in a sort of vain mediocrity, happy even when they escape starvation, notwithstanding their numerous degrees.

- Ch. 3 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1895)

- She was not shocked; it seemed to her that every woman had a right to arrange her life as she liked, when she was alone and free in the world. For her own part, however, she had never given way to such ideas; her sense of right and her healthy nature naturally maintained her in the respectability in which she had always lived.

- Ch. 5 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1895)

- Mais il avait oublié l’inventaire, il ne voyait pas son empire, ces magasins crevant de richesses. Tout avait disparu, les victoires bruyantes d’hier, la fortune colossale de demain. D’un regard désespéré, il suivait Denise, et quand elle eut passé la porte, il n’y eut plus rien, la maison devint noire.

- He had quite forgotten the stock-taking, he no longer beheld his empire, that building bursting with riches. Everything had disappeared, his former uproarious victories, his future colossal fortune. With a desponding look he was watching Denise and when she had crossed the threshold everything disappeared, a darkness came over the house.

- Ch. 10 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1895)

- Crever pour crever, je préfère crever de passion que de crever d'ennui!

- As one must die, I would rather die of passion than boredom!

- Ch. 11 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1895)

- You don't understand this language, old fellow: otherwise you'd know that action contains its own reward. To act, to create, to fight against facts, to overcome them or be overcome by them—the whole of human health and happiness is made up of that!

- Ch. 11 (tr. Brian Nelson, 1995)

- A woman's opinion, however humble she may be, is always worth listening to, if she's got any sense... If you put yourself in my hands, I shall certainly make a decent man of you.

- Ch. 12 (tr. Brian Nelson, 1995)

- His creation was a sort of new religion; the churches, gradually deserted by wavering faith, were replaced by his bazaar, in the minds of the idle women of Paris. Woman now came and spent her leisure time in his establishment, those shivering anxious hours which she had formerly passed in churches: a necessary consumption of nervous passion, an ever renewed struggle of the god of dress against the husband, an ever renewed worship of the body with the promise of future divine beauty.

- Ch. 14 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1895)

La joie de vivre (1883; 1884)

[edit]

- How the thought of meeting lost loved ones would sweeten one’s last moments, how eagerly would one embrace them, and what bliss to live together once more in immortality! He suffered agonies when he considered religion’s charitable lie, which compassionately conceals the terrible truth from feeble creatures. No, everything finished at death, nothing that we had loved was ever reborn, our farewells were for ever. For ever! For ever! That was the dreadful thought that carried his mind hurtling down abysses of emptiness.

- Ch. 7 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1955)

- Oh, that’s typical of you modern young men; you’ve nibbled at science and it’s made you ill, because you’ve not been able to satisfy that old craving for the absolute that you absorbed in your nurseries. You’d like science to give you all the answers at one go, whereas we’re only just beginning to understand it, and it’ll probably never be anything but an eternal quest. And so you repudiate science, you fall back on religion, and religion won’t have you any more. Then you relapse into pessimism... Yes, it’s the disease of our age, of the end of the century: you’re all inverted Werthers.

- Ch. 7 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1955)

- The sea with its perpetual surging, its stubborn waves that broke against the cliffs twice a day, irritated him as being a mere senseless force that recked nothing of his grief, and had gone on wearing the same rocks away for centuries, without ever shedding a single tear for the death of a human being. It was too vast, too cold; and he hurried back home again and shut himself up in his room, that he might feel less conscious of his own littleness, less crushed between the boundlessness of sea and sky.

- Ch. 7 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1901)

- Boredom was at the root of Lazare’s unhappiness, an oppressive, unremitting boredom, exuding from everything like the muddy water of a poisoned spring. He was bored with leisure, with work, with himself even more than with others. Meanwhile he blamed his own idleness for it, he ended by being ashamed of it.

- Ch. 8 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1955)

- She wanted to live, and live fully, and to give life, she who loved life! What was the good of existing, if you couldn’t give yourself?

- Ch. 8 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1955)

- The pride of abnegation had vanished, and she was willing that those she loved should be happy through other instrumentality than her own.

- Ch. 8 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1901)

- Did not one spend the first half of one’s days in dreams of happiness and the second half in regrets and terrors?

- Ch. 9 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1955)

- His was the sceptical boredom of all his generation, no longer the romantic boredom of the Werthers and Renés, regretfully lamenting the passing of old beliefs, but the boredom of the new, doubting heroes, the young chemists who angrily declare the world an impossible place because they have not suddenly found life at the bottom of their retorts.

- Ch. 9 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1955)

- The ground was trembling under their feet, and they clung to the resolutions made in their calmer hours so as not to sink into the abyss.

- Ch. 9 (tr. Jean Stewart, 1955)

- If the world is to die of misery, at any rate let it die cheerfully, and in sympathy with itself!

- Ch. 10 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1901)

- On a pitch black, starless night, a solitary man was trudging along the main road from Marchiennes to Montsou, ten kilometres of cobblestones running straight as a die across the bare plain between fields of beet.

- Pt. 1, ch. 1 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- Now Étienne could oversee the entire country. The darkness remained profound, but the old man's hand had, as it were, filled it with great miseries, which the young man unconsciously felt at this moment around him everywhere in the limitless tract. Was it not a cry of famine that the March wind rolled up across this naked plain? The squalls were furious: they seemed to bring the death of labour, a famine which would kill many men. And with wandering eyes he tried to pierce shades, tormented at once by the desire and by the fear of seeing. Everything was hidden in the unknown depths of the gloomy night. He only perceived, very far off, the blast furnaces and the coke ovens. The latter, with their hundreds of chimneys, planted obliquely, made lines of red flame; while the two towers, more to the left, burnt blue against the blank sky, like giant torches. It resembled a melancholy conflagration. No other stars rose on the threatening horizon except these nocturnal fires in a land of coal and iron.

- Pt. 1, ch. 1 (tr. Havelock Ellis, 1885)

- Blow the candle out, I don’t need to see what my thoughts look like.

- Pt. 1, ch. 2 (tr. Peter Collier, 1993)

- If people can just love each other a little bit, they can be so happy.

- Pt. 1, ch. 2 (tr. Roger Pearson, 2004)

- Pendant une demi-heure, le puits en dévora de la sorte, d'une gueule plus ou moins gloutonne, selon la profondeur de l'accrochage où ils descendaient, mais sans un arrêt, toujours affamé, de boyaux géants capables de digérer un peuple.

- For half an hour the shaft went on devouring in this fashion, with more or less greedy gulps, according to the depth of the level to which the men went down, but without stopping, always hungry, with its giant intestines capable of digesting a nation.

- Pt. 1, ch. 3 (tr. Havelock Ellis, 1885)

- It was at times like this that one of those waves of bestiality ran through the mine, the sudden lust of the male that came over a miner when he met one of these girls on all fours, with her rear in the air and her buttocks bursting out of her breeches.

- Pt. 1, ch. 4 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- Why had he found her unattractive? Now that she was all black and her face covered in a thin layer of coal-dust, she had a strange charm.

- Pt. 1, ch. 4 (tr. Roger Pearson, 2004)

- Il y avait des hommes si ambitieux qu'ils auraient torché les chefs, pour les entendre seulement dire merci.

- There were men so ambitious that they would wipe the masters' behinds to hear them say thank you.

- Pt. 2, ch. 3 (tr. Havelock Ellis, 1885)

- What misery! and all these girls, broken by fatigue, were silly enough to come here at night and make babies, more flesh to toil and suffer! It would never end while they went on getting themselves filled with starvelings. Ought they not rather to stop up their wombs and close their thighs tight against approaching disaster? But then, perhaps he was only harbouring these dismal thoughts because he resented being alone when all the others were pairing off to take their pleasure.

- Pt. 2, ch. 5 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- They spoke one after the other in a despairing voice, giving expression to their complaints. The workers could not hold out; the Revolution had only aggravated their wretchedness; only the bourgeois had grown fat since '89, so greedily that they had not even left the bottom of the plates to lick. Who could say that the workers had had their reasonable share in the extraordinary increase of wealth and comfort during the last hundred years? They had made fun of them by declaring them free. Yes, free to starve, a freedom of which they fully availed themselves. It put no bread into your cupboard to go and vote for fine fellows who went away and enjoyed themselves, thinking no more of the wretched voters than of their old boots. No! one way or another it would have to come to an end, either quietly by laws, by an understanding in good fellowship, or like savages by burning everything and devouring one another. Even if they never saw it, their children would certainly see it, for the century could not come to an end without another revolution, that of the workers this time, a general hustling which would cleanse society from top to bottom, and rebuild it with more cleanliness and justice.

- Pt. 3, ch. 1 (tr. Havelock Ellis, 1885)

- There's only one thing that warms my heart, and that is the thought that we are going to sweep away these bourgeois.

- Pt. 3, ch. 2 (tr. Havelock Ellis, 1885)

- All round there was a rising tide of beer, widow Désir’s barrels had all been broached, beer had rounded all paunches and was overflowing in all directions, from noses, eyes—and elsewhere. People were so blown out and higgledy-piggledy, that everybody’s elbows or knees were sticking into his neighbour and everybody thought it great fun to feel his neighbour’s elbows. All mouths were grinning from ear to ear in continuous laughter.

- Pt. 3, ch. 2 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- But now, deep in the earth, the miner was waking from his slumber and germinating in the soil like a real seed; and one fine day people would see what was growing in the middle of these fields: yes, men, a whole army of men, would spring up from the earth, and justice would be restored.

- Pt. 3, ch. 3 (tr. Roger Pearson, 2004)

- "And, then, if only there were some truth in what the priests say, if only the poor of this world were rich in the next!"

These words were greeted with a burst of laughter, and even the children shrugged their shoulders, for the hard wind blowing from the outer world had taken away all their belief. They harbored a secret fear of ghosts down in the mine, but scoffed at the empty heavens.- Pt. 3, ch. 3 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- When a man was honest in his dealings, you could forgive him the rest.

- Pt. 4, ch. 3 (tr. Roger Pearson, 2004)

- Antagonism breeds extremism, and it was turning one into the zealous revolutionary and the other into an excessive advocate of caution, taking them beyond what they really thought and forcing them to adopt positions of which they then became prisoners.

- Pt. 4, ch. 4 (tr. Roger Pearson, 2004)

- They, poor devils, were just machine-fodder, they were penned like cattle in housing-estates, the big Companies were gradually dominating their whole lives, regulating slavery, threatening to enlist all the nation’s workers, millions of hands to increase the wealth of a thousand idlers.

- Pt. 4, ch. 7 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- The fire from heaven had fallen on this Sodom in the bowels of the earth where long ago pit girls committed untold abominations, and it had fallen so swiftly that they had not had time to come up, so that to this very day they were still burning down in this hell.

- Pt. 5, ch. 1 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- They were brutes, no doubt, but brutes who could not read, and who were dying of hunger.

- Pt. 5, ch. 3 (tr. Havelock Ellis, 1885)

- It was the red vision of the revolution, which would one day inevitably carry them all away, on some bloody evening at the end of the century. Yes, some evening the people, unbridled at last, would thus gallop along the roads, making the blood of the middle class flow, parading severed heads and sprinkling gold from disembowelled coffers. The women would yell, the men would have those wolf-like jaws open to bite. Yes, the same rags, the same thunder of great sabots, the same terrible troop, with dirty skins and tainted breath, sweeping away the old world beneath an overflowing flood of barbarians.

- Pt. 5, ch. 5 (tr. Havelock Ellis, 1885)

- What idiot imagined that happiness in this world depended on a share-out of wealth? These starry-eyed revolutionaries could demolish society and build a brave new world if they liked, but they would not by so doing add one single joy to man’s lot, nor relieve him of a single pain merely by sharing out the cake. In fact they would only spread out the unhappiness of the world, and some day they would make the very dogs howl with despair by removing them from the simple satisfaction of their instincts and raising them to the unsatisfied yearnings of passion.

- Pt. 5, ch. 5 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- No, the only good was to be found in non-existence or, if one had to exist, in being a tree, a stone, or lower still, a grain of sand, for that cannot bleed under the heel of every passer-by.

- Pt. 5, ch. 5 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- « Du pain! est-ce que ça suffit, imbéciles ? »

- "Bread! is that enough, idiots!"

- Pt. 5, ch. 5 (tr. Havelock Ellis, 1885)

- He would have given up everything -- education, comfort, luxurious life and his powerful position as manager -- if only just for one day he could have been the humblest of these poor devils under him and be free with his own body and be oafish enough to beat his wife and take his pleasure with the wives of his neighbors. He found himself wishing he were dying of starvation too, and that his empty belly were twisted with pains that made his brain reel, for perhaps that might deaden this relentless grief! Oh to live like a brute, possessing nothing but freedom to roam in the cornfields with the ugliest and most revolting haulage girl and possess her!

- Pt. 5, ch. 5 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- Oh, those bourgeois scum! One day they’d stuff 'em with champagne and truffles till their guts burst!

- Pt. 5, ch. 6 (tr. Roger Pearson, 2004)

- Oui, c'est votre idée, à vous tous, les ouvriers français, déterrer un trésor, pour le manger seul ensuite, dans un coin d'égoïsme et de fainéantise. Vous avez beau crier contre les riches, le courage vous manque de rendre aux pauvres l'argent que la fortune vous envoie... Jamais vous ne serez dignes du bonheur, tant que vous aurez quelque chose à vous, et que votre haine des bourgeois viendra uniquement de votre besoin enragé d'être des bourgeois à leur place.

- Yes, that is your idea, all of you French workmen; you want to unearth a treasure in order to devour it alone afterwards in some lazy, selfish corner. You may cry out as much as you like against the rich, you haven't got courage enough to give back to the poor the money that luck brings you. You will never be worthy of happiness as long as you own anything, and your hatred of the bourgeois proceeds solely from an angry desire to be bourgeois yourselves in their place.

- Pt. 6, ch. 3 (tr. Havelock Ellis, 1885)

- This sounded the death knell of small family businesses, soon to be followed by the disappearance of the individual entrepreneur, gobbled up one by one by the increasingly hungry ogre of capitalism, and drowned by the rising tide of large companies.

- Pt. 7, ch. 1 (tr. Peter Collier, 1993)

- She was haunted by the vision of Chaval, and rambled on about him, about their cat and dog life together, the one day when he had been nice to her, in Jean-Bart, and the other days or alternate caresses and blows, when he half killed her with his embraces after nearly beating her to death.

- Pt. 7, ch. 5 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- Des hommes poussaient, une armée noire, vengeresse, qui germait lentement dans les sillons, grandissant pour les récoltes du siècle futur, et dont la germination allait faire bientôt éclater la terre.

- Men were springing up, a black avenging host was slowly germinating in the furrows, thrusting upward for the harvests of future ages. And very soon their germination would crack the earth asunder.

- Pt. 7, ch. 6 (tr. L. W. Tancock, 1954)

- What was Art, after all, if not simply giving out what you have inside you? Didn’t it all boil down to sticking a female in front of you and painting her as you feel she is?

- Ch. 2 (tr. Thomas Walton and Roger Pearson, 1993)

- « Ah! bonne terre, prends-moi, toi qui es la mère commune, l'unique source de la vie! toi l'éternelle, l'immortelle, où circule l'âme du monde, cette sève épandue jusque dans les pierres, et qui fait des arbres nos grands frères immobiles! ... Oui, je veux me perdre en toi, c'est toi que je sens là, sous mes membres, m'étreignant et m'enflammant, c'est toi seule qui seras dans mon oeuvre comme la force première, le moyen et le but, l'arche immense, où toutes les choses s'animent du souffle de tous les êtres! »

- "Oh, beneficent earth, take me unto thee, thou who art our common mother, our only source of life! thou the eternal, the immortal one, in whom circulates the soul of the world, the sap that spreads even into the stones, and makes the trees themselves our big, motionless brothers! Yes, I wish to lose myself in thee; it is thou that I feel beneath my limbs, clasping and inflaming me; thou alone shalt appear in my work as the primary force, the means and the end, the immense ark in which everything becomes animated with the breath of every being!"

- Ch. 6 (tr. E. A. Vizetelly, 1886)

- Haven’t I told you scores of times that you’re always beginners, and the greatest satisfaction was not in being at the top, but in getting there, in the enjoyment you get out of scaling the heights? ... If only we could have the courage to hang ourselves in front of our last masterpiece!

- Ch. 7 (tr. Thomas Walton and Roger Pearson, 1993)

- From the moment I start a new novel, life’s just one endless torture.

- Ch. 9 (tr. Thomas Walton and Roger Pearson, 1993)

- The thing is, work has simply swamped my whole existence. ... It’s like a germ planted in the skull that devours the brain, spreads to the trunk and the limbs, and destroys the entire body in time.

- Ch. 9 (tr. Thomas Walton and Roger Pearson, 1993)

- The past was but the cemetery of our illusions: one simply stubbed one’s toes on the gravestones.

- Ch. 11 (tr. Thomas Walton and Roger Pearson, 1993)

- Oh, the fools, like a lot of good little schoolboys, scared to death of anything they’ve been taught is wrong!

- Ch. 12 (tr. Thomas Walton and Roger Pearson, 1993)

- It was the noisome fruit of ignorance and filth, ever recurring, the Black Death, the Great Plague, which stride like giant skeletons through past centuries, scything down the pale, sad people of the countryside.

- Pt. 1, sec. 5 (tr. Douglas Parmée, 1980)

- Élodie, who was rising fifteen, lifted her anaemic, puffy, virginal face with its wispy hair; she was so thin-blooded that good country air seemed only to make her more sickly.

- Pt. 2, sec. 7 (tr. Douglas Parmée, 1980)

- They all listened to him, with curiosity but with the blank indifference of practical people who in their hearts no longer feared his God of wrath and chastisement. ... The whole thing was a complete waste of time; there was much more point in keeping on the right side of the Government police, who were the people with the power.

- Pt. 3, sec. 6 (tr. Ann Lindsay, 1955)

- If the earth was restful and good to those who loved it, the villagers contaminating it like vermin, those human insects battening on it's flesh, were enough to disgrace it and blight any approach to it.

- Pt. 5, sec. 3 (tr. Douglas Parmée, 1980)

- Just as the frost that burns the crops, the hail that chops them down, the thunderstorms which batter them are all perhaps necessary, maybe blood and tears are needed to keep the world going.

- Pt. 5, sec. 6 (tr. Douglas Parmée, 1980)

- Only the earth is immortal, the Great Mother from whom we spring and to whom we return, love of whom can drive us to crime and through whom life is perpetually preserved for her own inscrutable ends, in which even our wretched degraded nature has its part to play.

- Pt. 5, sec. 6 (tr. Douglas Parmée, 1980)

- Des morts, des semences, et le pain poussait de la terre.

- Death and the sowing of seeds: and the life of bread growing up out of the earth.

- Pt. 5, sec. 6 (tr. Ann Lindsay, 1955)

La Bête humaine (1890)

[edit]

- She was a combative virgin, was Flora, scornful of the male sex, all of which in the end had led folk to conclude that she could not be quite all there.

- Ch. 2 (tr. Alec Brown, 1956)

- Ne me regardez plus comme ça, parce que vous allez vous user les yeux.

- Don't keep looking at me like that, you’ll wear your eyes out.

- Ch. 5 (tr. Alec Brown, 1956)

- Could he love this one, without killing her?

- Ch. 5 (tr. Edward Vizetelly, 1901)

- ... la machine ronflait, crachait, comme une bête qu’on surmène, avec des sursauts, des coups de reins, où l’on aurait cru entendre craquer ses membres.

- The door was now becoming red-hot, lighting up the legs of both of them with a violet gleam. But neither felt the scorching heat in the current of icy air that enveloped them. The fireman, at a sign from his chief, had just raised the rod of the ash-pan which added to the draught. The hand of the manometer at present marked ten atmospheres, and La Lison was exerting all the power it possessed. At one moment, perceiving the water in the steam-gauge sink, the driver had to turn the injection-cock, although by doing so he diminished the pressure. Nevertheless, it rose again, the engine snorted and spat like an animal over-ridden, making jumps and efforts fit to convey the idea that it would suddenly crack some of its component pieces. And he treated La Lison roughly, like a woman who has grown old and lost her strength, ceasing to feel the same tenderness for it as formerly.

- Ch. 7 (tr. Edward Vizetelly, 1901)

- He had devoured her, the strapping creature, tall and handsome, that she once had been, eating into her much as an insect eats into an oak, till here she was for ever on her back, reduced to nothingness, whereas he was still going.

- Ch. 10 (tr. Alec Brown, 1956)

- Does anyone kill as the result of reasoning? People only kill by an impulse of blood and nerves—the necessity to live, the joy of being strong.

- Ch. 11 (tr. Edward Vizetelly, 1901)

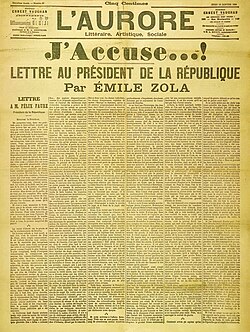

J'accuse...! (1898)

[edit]

- "J'accuse!" [I Accuse!] is a famous open letter to French President Félix Faure on the scandal known as the Dreyfus Affair, published in L'Aurore [The Dawn] (13 January 1898). It has been called "the greatest newspaper article of all time" and accused military officers of covering up the evidence that forged documents had been used to wrongly convict Alfred Dreyfus of espionage. - Full text, in French and English

- Sir,

Would you allow me, grateful as I am for the kind reception you once extended to me, to show my concern about maintaining your well-deserved prestige and to point out that your star which, until now, has shone so brightly, risks being dimmed by the most shameful and indelible of stains?

- A court martial, under orders, has just dared to acquit a certain Esterhazy, a supreme insult to all truth and justice. And now the image of France is sullied by this filth, and history shall record that it was under your presidency that this crime against society was committed.

As they have dared, so shall I dare. Dare to tell the truth, as I have pledged to tell it, in full, since the normal channels of justice have failed to do so. My duty is to speak out; I do not wish to be an accomplice in this travesty. My nights would otherwise be haunted by the spectre of the innocent man, far away, suffering the most horrible of tortures for a crime he did not commit.

- The truth, first of all, about Dreyfus' trial and conviction: At the root of it all is one evil man, Lt. Colonel du Paty de Clam, who was at the time a mere Major. He is the entire Dreyfus case, and the entirety of it will only come to light when an honest enquiry firmly establishes his actions and responsibilities. ... Nobody would ever believe the experiments to which he subjected the unfortunate Dreyfus, the traps he set for him, the wild investigations, the monstrous fantasies, the whole demented torture.

Ah, that first trial! What a nightmare it is for all who know it in its true details. Major du Paty de Clam had Dreyfus arrested and placed in solitary confinement. He ran to Mme Dreyfus, terrorised her, telling her that, if she talked, that was it for her husband. Meanwhile, the unfortunate Dreyfus was tearing his hair out and proclaiming his innocence.

- I would like to point out how this travesty was made possible, how it sprang out of the machinations of Major du Paty de Clam, how Generals Mercier, de Boisdeffre and Gonse became so ensnared in this falsehood that they would later feel compelled to impose it as holy and indisputable truth. Having set it all in motion merely by carelessness and lack of intelligence, they seem at worst to have given in to the religious bias of their milieu and the prejudices of their class. In the end, they allowed stupidity to prevail.

- The public was astounded; rumors flew of the most horrible acts, the most monstrous deceptions, lies that were an affront to our history. The public, naturally, was taken in. No punishment could be too harsh. The people clamored for the traitor to be publicly stripped of his rank and demanded to see him writhing with remorse on his rock of infamy. Could these things be true, these unspeakable acts, these deeds so dangerous that they must be carefully hidden behind closed doors to keep Europe from going up in flames? No! They were nothing but the demented fabrications of Major du Paty de Clam, a cover-up of the most preposterous fantasies imaginable. To be convinced of this one need only read carefully the accusation as it was presented before the court martial.

How flimsy it is! The fact that someone could have been convicted on this charge is the ultimate iniquity. I defy decent men to read it without a stir of indignation in their hearts and a cry of revulsion, at the thought of the undeserved punishment being meted out there on Devil's Island. He knew several languages: a crime! He carried no compromising papers: a crime! He would occasionally visit his country of origin: a crime! He was hard-working, and strove to be well informed: a crime! He did not become confused: a crime! He became confused: a crime! And how childish the language is, how groundless the accusation!

- It is said that within the council chamber the judges were naturally leaning toward acquittal. It becomes clear why, at that point, as justification for the verdict, it became vitally important to turn up some damning evidence, a secret document that, like God, could not be shown, but which explained everything, and was invisible, unknowable, and incontrovertible. I deny the existence of that document.... a document concerning national defense that could not be produced without sparking an immediate declaration of war tomorrow? No! No! It is a lie, all the more odious and cynical in that its perpetrators are getting off free without even admitting it. They stirred up all of France, they hid behind the understandable commotion they had set off, they sealed their lips while troubling our hearts and perverting our spirit. I know of no greater crime against the state.

- And now we come to the Esterhazy case. Three years have passed, many consciences remain profoundly troubled, become anxious, investigate, and wind up convinced that Dreyfus is innocent.

- Feelings were running high, for the conviction of Esterhazy would inevitably lead to a retrial of Dreyfus, an eventuality that the General Staff wanted at all cost to avoid.

This must have led to a brief moment of psychological anguish. Note that, so far, General Billot was in no way compromised. Newly appointed to his position, he had the authority to bring out the truth. He did not dare, no doubt in terror of public opinion, certainly for fear of implicating the whole General Staff, General de Boisdeffre, and General Gonse, not to mention the subordinates. So he hesitated for a brief moment of struggle between his conscience and what he believed to be the interest of the military. Once that moment passed, it was already too late. He had committed himself and he was compromised. From that point on, his responsibility only grew, he took on the crimes of others, he became as guilty as they, if not more so, for he was in a position to bring about justice and did nothing. Can you understand this: for the last year General Billot, Generals Gonse and de Boisdeffre have known that Dreyfus is innocent, and they have kept this terrible knowledge to themselves?

- Lt. Colonel Picquart had carried out his duty as an honest man. He kept insisting to his superiors in the name of justice. He even begged them, telling them how impolitic it was to temporize in the face of the terrible storm that was brewing and that would break when the truth became known.

- Meanwhile, in Paris, truth was marching on, inevitably, and we know how the long-awaited storm broke. Mr. Mathieu Dreyfus denounced Major Esterhazy as the real author of the bordereau just as Mr. Scheurer-Kestne was handing over to the Minister of Justice a request for the revision of the trial. This is where Major Esterhazy comes in. Witnesses say that he was at first in a panic, on the verge of suicide or running away. Then all of a sudden, emboldened, he amazed Paris by the violence of his attitude.

- It came down, once again, to the General Staff protecting itself, not wanting to admit its crime, an abomination that has been growing by the minute.

In disbelief, people wondered who Commander Esterhazy's protectors were. First of all, behind the scenes, Lt. Colonel du Paty de Clam was the one who had concocted the whole story, who kept it going, tipping his hand with his outrageous methods. Next General de Boisdeffre, then General Gonse, and finally, General Billot himself were all pulled into the effort to get the Major acquitted, for acknowledging Dreyfus's innocence would make the War Office collapse under the weight of public contempt. And the astounding outcome of this appalling situation was that the one decent man involved, Lt. Colonel Picquart who, alone, had done his duty, was to become the victim, the one who got ridiculed and punished. O justice, what horrible despair grips our hearts? It was even claimed that he himself was the forger, that he had fabricated the letter-telegram in order to destroy Esterhazy . But, good God, why? To what end? Find me a motive. Was he, too, being paid off by the Jews? The best part of it is that Picquart was himself an anti-Semite. Yes! We have before us the ignoble spectacle of men who are sunken in debts and crimes being hailed as innocent, whereas the honor of a man whose life is spotless is being vilely attacked: A society that sinks to that level has fallen into decay.

- The Esterhazy affair, thus, Mr. President, comes down to this: a guilty man is being passed off as innocent. For almost two months we have been following this nasty business hour by hour. I am being brief, for this is but the abridged version of a story whose sordid pages will some day be written out in full.

- How could anyone expect a court martial to undo what another court martial had done?

I am not even talking about the way the judges were hand-picked. Doesn't the overriding idea of discipline, which is the lifeblood of these soldiers, itself undercut their capacity for fairness? Discipline means obedience. When the Minister of War, the commander in chief, proclaims, in public and to the acclamation of the nation's representatives, the absolute authority of a previous verdict, how can you expect a court martial to rule against him?

- General Billot directed the judges in his preliminary remarks, and they proceeded to judgment as they would to battle, unquestioningly. The preconceived opinion they brought to the bench was obviously the following: "Dreyfus was found guilty for the crime of treason by a court martial; he therefore is guilty and we, a court martial, cannot declare him innocent. On the other hand, we know that acknowledging Esterhazy's guilt would be tantamount to proclaiming Dreyfus innocent." There was no way for them to escape this rationale.

So they rendered an iniquitous verdict that will forever weigh upon our courts martial and will henceforth cast a shadow of suspicion on all their decrees. The first court martial was perhaps unintelligent; the second one is inescapably criminal.

- We are told of the honor of the army; we are supposed to love and respect it. Ah, yes, of course, an army that would rise to the first threat, that would defend French soil, that army is the nation itself, and for that army we have nothing but devotion and respect. But this is not about that army, whose dignity we are seeking, in our cry for justice. What is at stake is the sword, the master that will one day, perhaps, be forced upon us. Bow and scrape before that sword, that god? No!

- Ah, what a cesspool of folly and foolishness, what preposterous fantasies, what corrupt police tactics, what inquisitorial, tyrannical practices! What petty whims of a few higher-ups trampling the nation under their boots, ramming back down their throats the people's cries for truth and justice, with the travesty of state security as a pretext.

- It is a crime that those people who wish to see a generous France take her place as leader of all the free and just nations are being accused of fomenting turmoil in the country, denounced by the very plotters who are conniving so shamelessly to foist this miscarriage of justice on the entire world. It is a crime to lie to the public, to twist public opinion to insane lengths in the service of the vilest death-dealing machinations. It is a crime to poison the minds of the meek and the humble, to stoke the passions of reactionism and intolerance, by appealing to that odious anti-Semitism that, unchecked, will destroy the freedom-loving France of the Rights of Man. It is a crime to exploit patriotism in the service of hatred, and it is, finally, a crime to ensconce the sword as the modern god, whereas all science is toiling to achieve the coming era of truth and justice.

Truth and justice, so ardently longed for! How terrible it is to see them trampled, unrecognized and ignored!

- These military tribunals have, decidedly, a most singular idea of justice.

This is the plain truth, Mr. President, and it is terrifying. It will leave an indelible stain on your presidency. I realise that you have no power over this case, that you are limited by the Constitution and your entourage. You have, nonetheless, your duty as a man, which you will recognise and fulfill. As for myself, I have not despaired in the least, of the triumph of right. I repeat with the most vehement conviction: truth is on the march, and nothing will stop it. Today is only the beginning, for it is only today that the positions have become clear: on one side, those who are guilty, who do not want the light to shine forth, on the other, those who seek justice and who will give their lives to attain it. I said it before and I repeat it now: when truth is buried underground, it grows and it builds up so much force that the day it explodes it blasts everything with it. We shall see whether we have been setting ourselves up for the most resounding of disasters, yet to come.

- But this letter is long, Sir, and it is time to conclude it.

I accuse Lt. Col. du Paty de Clam of being the diabolical creator of this miscarriage of justice — unwittingly, I would like to believe — and of defending this sorry deed, over the last three years, by all manner of ludricrous and evil machinations.

I accuse General Mercier of complicity, at least by mental weakness, in one of the greatest inequities of the century.

I accuse General Billot of having held in his hands absolute proof of Dreyfus's innocence and covering it up, and making himself guilty of this crime against mankind and justice, as a political expedient and a way for the compromised General Staff to save face.

I accuse Gen. de Boisdeffre and Gen. Gonse of complicity in the same crime, the former, no doubt, out of religious prejudice, the latter perhaps out of that esprit de corps that has transformed the War Office into an unassailable holy ark.

I accuse Gen. de Pellieux and Major Ravary of conducting a villainous enquiry, by which I mean a monstrously biased one, as attested by the latter in a report that is an imperishable monument to naïve impudence.

I accuse the three handwriting experts, Messrs. Belhomme, Varinard and Couard, of submitting reports that were deceitful and fraudulent, unless a medical examination finds them to be suffering from a condition that impairs their eyesight and judgement.

I accuse the War Office of using the press, particularly L'Eclair and L'Echo de Paris, to conduct an abominable campaign to mislead the general public and cover up their own wrongdoing.

Finally, I accuse the first court martial of violating the law by convicting the accused on the basis of a document that was kept secret, and I accuse the second court martial of covering up this illegality, on orders, thus committing the judicial crime of knowingly acquitting a guilty man.

- In making these accusations I am aware that I am making myself liable to articles 30 and 31 of the law of 29/7/1881 regarding the press, which make libel a punishable offence. I expose myself to that risk voluntarily.

As for the people I am accusing, I do not know them, I have never seen them, and I bear them neither ill will nor hatred. To me they are mere entities, agents of harm to society. The action I am taking is no more than a radical measure to hasten the explosion of truth and justice.

I have but one passion: to enlighten those who have been kept in the dark, in the name of humanity which has suffered so much and is entitled to happiness. My fiery protest is simply the cry of my very soul. Let them dare, then, to bring me before a court of law and let the enquiry take place in broad daylight! I am waiting.

Disputed

[edit]- Civilization will not attain perfection until the last stone from the last church falls on the last priest.

- Cited as attributed to Zola in The Heretic's Handbook of Quotations: Cutting Comments on Burning Issues (1992) by Charles Bufe, p. 183, but no earlier citation has yet been located, and this appears to be very similar to remarks often attributed to Denis Diderot: "Men will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest" and "Let us strangle the last king with the guts of the last priest" — these are loosely derived from a statement Diderot actually did make: "his hands would plait the priest's entrails, for want of a rope, to strangle kings."

- This quote appeared in soviet popular-scientific work "Satellite atheist" (Sputnik ateista) (1959), p. 491.

- We are like books. Most people only see our cover, the minority read only the introduction, many people believe the critics. Few will know our content.

Quotes about Zola

[edit]- sorted alphabetically

- I've ripped it to pieces - your portrait, you know. I tried to work on it this morning, but it went from bad to worse, so I destroyed it...

- Paul Cézanne, letter to Emile Zola (ca 1861) as quoted by Ambroise Vollard, Cézanne, (1984) Dover publications Inc. New York p. 23 [a republication of Paul Cézanne: His Life and Art (1937) a translation by Harold L. Van Doren of Paul Cézanne (1914) ed., Ambroise Vollard].

- This quote refers to an early Paris portrait of his friend Zola.

- You can't ask a man to talk sensibly about the art of painting if he simply doesn't know anything about it. But by God, how can he [Émile Zola who was his youth friend in Aix-de-Provence and who had used Cezanne's life as model of a disturbed artist in his novel L'Oeuvre] dare to say that a painter is done because he has painted one bad picture? When a picture isn't realized, you pitch it in the fire and start another one.

- Paul Cézanne (1902) after Zola's death in a conversation in Cezanne's studio in Aix, as quoted by Ambroise Vollard, Cézanne, (1984) Dover publications Inc. New York, p. 74 [a republication of Paul Cézanne: His Life and Art (1937) a translation by Harold L. Van Doren of Paul Cézanne (1914) ed., Ambroise Vollard].

- This quote refers to an early Paris portrait of his friend Zola.

- Many older students also read the meticulous details of Émile Zola's downtrodden classes, which strongly echoed some of the realties of my own impoverished neighborhood.

- Edwidge Danticat Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work (2010)

- He was a moment in the conscience of Man.

- Anatole France (5 October 1902) Speech at Zola's funeral.

- His work is evil, and he is one of those unhappy beings of whom one can say that it would be better had he never been born. I will not, certainly, deny his detestable fame. No one before him has raised so lofty a pile of ordure. That is his monument, and its greatness cannot be disputed.

- Anatole France, On Life and Letters (1911).

- The real pioneers in ideas, in art and in literature have remained aliens to their time, misunderstood and repudiated. And if, as in the case of Zola, Ibsen and Tolstoy, they compelled their time to accept them, it was due to their extraordinary genius and even more so to the awakening and seeking of a small minority for new truths, to whom these men were the inspiration and intellectual support.

- Then came the sweetly hypocritical compliments, the questions which are traps, the declarations which, if you follow him, he will suddenly interrupt with an 'Oh, my dear fellow, I wouldn't go as far as you!' followed by a virtual recantation of his previous arguments. In fact that art of talking without saying anything of which the Man of Medan is the master.

- Edmond de Goncourt, Pages from the Goncourt Journal(1962) Tr. R. Baldick.

- Adolphe Thiers... was named "chief of the executive power of the French Republic" and given the authority to negotiate the terms of surrender with Otto von Bismarck. ...Since escaping to Marseilles in September [1871] Zola had launched a newspaper, La Marseillaise... intended... as a voice of the proletariat. However, this organ ceased publication... when, ironically, the printers struck for higher wages [and] Zola, turning strike-buster, tried unsuccessfully to overcome by engaging a team of cut-rate printers from Arles. With his career as a newspaper proprietor thwarted, he began cultivating plans to secure... a [political] post... [e]ventually... secretary to an elderly and reputedly senile left-wing deputy in the National Assembly. He was also reporting on the National Assembly for La Cloche and fretting about the refugees occupying his apartment in Paris. "Has anything been ransacked or stolen?"

- Ross King, The Judgment of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism (2006) p. 298; citing Frederick Brown, Zola, A Life (1996) p. 208.

- In 1886 he published... L'Oeuvre, the hero of which was a painter. ...Zola's own notes are evidence that the portrait... was based partly on Manet and partly on Cézanne... [T]he hero, symbolizing an impressionist, is characterized as a painful mixture of genius and madness. The struggle between his great dreams and his insufficient creative power ends in utter failure, in suicide. ...Cézanne was deeply hurt ...[and] found there a moving echo of his own youth, which had been inseparable from that of Zola, but also the betrayal of his hopes. ...[H]e now saw irrevocably expressed in this novel: Zola's pity for those who had not achieved success, a pity more unbearable than contempt. Zola had not only failed to grasp the true meaning of the effort to which Cézanne and his comrades had devoted all their strength, he had lost all feeling of solidarity. From the secure castle he had built himself in Médan, he passed judgement upon his friends, embracing all the bourgeois prejudices against which they had once fought together. The letter which Cézanne wrote to Zola to thank him for sending a copy of L'Oeuvre was meloncholy and sad; it was... a letter of farewell, and the two friends were never to meet again.

- John Rewald, History of Impressionism (1946) p. 398; citing Cézanne's (April 4, 1886) letter to Zola; Cézanne Letters, London, 1941, p. 183

- Zola's true crime has been in daring to rise to defend the truth and civil liberty... for that courageous defense of the primordial rights of the citizen, he will be honored wherever men have souls that are free...

- The Times, London (1898) article on Zola's libel trial, as quoted by John A. Corry, Prelude to a Century (1998) p. 72

- Last month marked the centennial anniversary of the greatest newspaper article of all time... Written in the form of an open letter to the President of France, the 4,000 word article, entitled "J'Accuse!" (I Accuse!), rightly has been judged a "masterpiece" of polemics and a literary achievement "of imperishable beauty." No other newspaper article has ever provoked such public debate and controversy or had such an impact on law, justice, and society.

- Donald E. Wilkes Jr., professor at the University of Georgia School of Law, J'accuse...! Emile, Zola, Alfred Dreyfus, and the Greatest Newspaper Article in History in Flagpole Magazine (11 February 1998).

External links

[edit]- Brief biography at Kirjasto (Pegasos)

- The Online Books Page (University of Pennsylvania)

- Works by Émile Zola at Project Gutenberg

- "J´accuse ...!" Emile Zola, Alfred Dreyfus, and the greatest newspaper article in history, by Donald E. Wilkes Jr. from Flagpole Magazine

- J´accuse in English and French at Chameleon Translations

- Movie adaptation of "J'accuse!" in The Life of Emile Zola (1937)